This is most of the info of Halsall from other sites. To search for something specifically, use the search box at the top

Click on image for a bigger photograph.

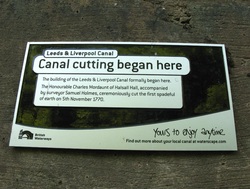

Mordaunt's Halsall (Lancashire) copper Conder penny token undated, probably 1792. Obverse: Coat of arms supported by two falcons above banner reading: “CONTENTA NEC PLACIDA QUIETE EST”. Reverse: Legend on two lines: “HALSALL D”. Heavily patterned edge. Penny, arms of the Earls of Peterborough, rev. value, edge engrailed, 16.16g/6h (DH 1). Small die flaw in reverse field. These were issued by Colonel Charles Lewis Mordaunt to pay his workers at Halsall Cotton Mill. Col Charles Lewis Mordaunt (c.1729-1808), a former Guards officer appointed JP in March 1763, came into possession of the Mohun estate at Halsall in the late 1760s. A decade later he had built a water-powered spinning/cotton mill there and by 1782 was employing 160 women and children. As early as December 1783 John Moon, Mordaunt’s superintendant, was in touch with Boulton & Watt, enquiring about having tokens made; it would seem that they were issued shortly after this time and, if this were the case, they would pre-date the pioneering Anglesey series. A document on the state of the copper coinage in circulation in Liverpool in 1791 infers that Mordaunt’s pennies were, by then, not in circulation (cf. Chaloner, SCMB 1972, pp.402-3). Famously, Morduant dug the first sod of the Leeds-Liverpool canal in Halsall on 5 November, 1770.

Halsall, Ormskirk, Lancashire

I was born in Ormskirk, Lancashire. I lived and went to school in Halsall and then Merchant Taylors' and was a choir boy under the reign of Canon Bullough. I had a very enjoyable childhood in Halsall where I lived for 19 years. My mum lived there for a further 15 years

Here is the fascinating history of Halsall according to the Internet

Click here to see the Halsall conservation area

Click here to see The Office of National Statistics data for Halsall

Click here to see census, birth, marriage and burial data for Halsall

Click here for the top surnames in Halsall in 1881

If you would like to search for anything on this page, click on Edit at the top, and then Find and type what you are looking for in the box in the bottom left of the screen

From: http://uk-genealogy.org.uk/england/Lancashire/towns/Halsall.html

Halsall, a village, a township, and a parish in Lancashire. The village stands near the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, is a scattered place, and has a station, called Barton and Halsall, on the Cheshire Lines Committee's railway, and a post and telegraph office under Ormskirk; money order office, Orms-kirk. The township includes also the hamlets of Barton and Haskeyne. Acreage, 6995; population, 1264. The parish contains likewise the townships of Down Holland, Lydiate, Moiling, and Maghull. Acreage, 16, 679; population of the civil parish, 5451; of the ecclesiastical, 1568. A considerable area of marsh land has been reclaimed and laid out as farms. The manor belongs to the Castega family. Good building stone is found. The living is a rectory in the diocese of Liverpool; gross value, £3500 with residence. The church is a fine example of the Decorated order, consists of nave, three aisles, and chancel, with tower and spire, contains a piscina, effigies of a priest and a knight, and several mural monuments, and was thoroughly restored in 1886. There is an endowed school for boys, founded in 1593, and other charities.

From: http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/LAN/Halsall/

and

http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/place/place_page.jsp?p_id=10301&st=HALSALL

In 1870-72, John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales described Halsall like this:

HALSALL, a village, a township, a parish, and a subdistrict, in Ormskirk district, Lancashire. The village stands near the Leeds and Liverpool canal, 3 miles NW of Ormskirk r. station; is a scattered place; and has a post office under Ormskirk. The township includes also the hamlets of Barton and Haskeyne. Acres, 6, 996. Real property, £10,661. Pop., 1,204. Houses, 196. The parish contains likewise the townships of DownHolland and Melling, and the chapelries of Maghull and Lydiate. Acres, 1,658. Real property, £36,268. Pop. in 1851, 1, 510; in 1861, 1, 672. Houses, 803. The property is much subdivided. The manor belongs to Lady Scarisbrick. Good building stone is found; and a kind of moss exists which has been used for candles. The living is a rectory in the diocese of Chester. Value, £3,500.* Patron, H. H. Blundell, Esq. The church consists of nave, three aisles, and chancel, with tower and spire; contains a piscina, an effigies of a priest, and several mural monuments; and is in good condition. The p. curacies of Maghull, Melling, and Lydiate, are separate benefices. There are a national school for girls, an endowed school for boys, with £26, and other charities with £200. The sub-district comprises Halsall and Down Holland Townships. Acres, 10,470. Pop., 952. Houses, 329.

From: http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/LAN/Halsall/StCuthbert.shtml

Church History: St Cuthbert's was founded in Norman times. The first Rector of Halsall was Robert (no second name known), c.1190. There was originally a Norman Church founded on the site (no documents are known with the date of foundation). The early English church was started around 1290. The church has undergone numerous alterations over the centuries. Scheme of alterations:

From: http://www.allertonoak.com/merseySights/OutlyingAreasMH.html

St. Cuthbert's Church, Halsall

Halsall was recorded in the Domesday Book, when it was one of the principal manors in the district. The village used to sit at the edge of a great moss that spread out to the west and became flooded in winter. Like much of the neighbouring area, the land has now been drained and is fertile crop growing territory. The church of St. Cuthbert dates from about 1320, probably replacing an earlier church, and stands on slightly higher ground, along with most of the older habitations. The 126 ft (38 m) tower and spire were added in about 1400, though the present spire is a more recent replacement. In mediaeval times, it appears that the area was leased to the Lord of Warrington, who extraordinarily enough paid 1 lb of cumin for the annual rent. I wonder if they had a curry house back then. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal passes behind the village and, indeed, the first excavations took place here in 1770.

Halsall in Lewis's Topographical Dictionary of England (1848)

It is situated near the coast, and intersected by the Leeds and Liverpool canal, which passes through each of its townships; the views of the sea are good, and the air salubrious. There are some quarries of freestone; and in Halsall moss, which is rather extensive, is found a bituminous turf, which burns like a candle. The parochial church is handsome, partly in the decorated and partly in the later English style, with a lofty spire, and forms a conspicuous object in the scenery.

Halsall in the Victoria History of the County of Lancaster (1907)

This township had formerly a great moss on the west, covering about half the surface, and constituting an effectual boundary. Down to recent times there were also three large meres - Black Otter, White Otter, and Gettern. The fenland has now been reclaimed and converted into fertile fields under a mixed cultivation - corn, root crops, fodder, and hay. There is some pasture land, and occasional osier beds fill up odd corners. The soil is loamy, with clay beneath. The low-lying ground is apt to become flooded after wet weather or in winter-time, and deep ditches are necessary to carry away superfluous water. In summer these ditches are filled with a luxuriant fenland flora, which thus finds shelter in an exposed country. The scanty trees show by their inclination the prevalence of winds from the west laden with salt. The ground rises gently to the east; until on the boundary 95 ft. is reached. [...]

The Liverpool, Southport, and Preston Junction Railway, now taken over by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Company, formed a branch through the township with a station called Halsall, half a mile west of the church, and another at Shirdley Hill. The scattered houses of the village stand on the higher ground near the church. To the south-east is the hamlet of Bangors Green; Four Lane Ends is to the north-east. From near the church an extensive and comprehensive view of the surrounding county is obtained. The northern arm of the Downholland Brook rises in and drains part of the district, running eventually into the River Alt, which is the natural receptacle for all the streams and ditches hereabouts. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal crosses the southeastern portion of the township, with the usual accompaniment of sett-laid roads and untidy wharfs. [...] The hall is to the south-west of the church; between them was a water-mill, taken down about 1880. North-east of the church are portions of the old rectory house, consisting of a wall 55 ft. long, with three doorways and three two-light windows, several traces of cross walls, and a turret at the north-west. Part is of fourteenth-century date.

From: http://www.numsoc.net/halsall.html

The Halsall Penny and Colonel Mordaunt’s Mill

How Happenings In A Lancashire Village Changed The World

Whenever is told the story of the Industrial Revolution, the Lancashire village of Halsall and the name of Colonel Mordaunt seldom feature largely, and yet in a succession of three individually small events they influenced the course of affairs which changed the basis of human society and brought about the world we live in today. These are great claims, but can they be justified?

Our story really begins with Colonel Mordaunt. Charles Lewis Mordaunt was born in 1730 to father Charles, a nephew of the Earl of Peterborough, and mother Anne, formerly Anne Howe. As did many scions of the nobility, Charles Mordaunt entered upon a military career, serving in the Guards, and travelling out to India where he developed a taste for exotic pastimes, including cockfighting.

Promotion in the army came quickly, as it could to those of adequate means in the days of purchased commissions and by 1765, when he retired from the service, Mordaunt had reached the rank of Colonel. His retirement may have been prompted by his acquisition, in the early 1760s, of the Mohun estate at Halsall by marriage to the widow of Lord Mohun, and it was at Halsall Hall that Mordaunt took up his residence. The Mordaunt coat of arms was placed over the door leading to the courtyard at the rear of the Hall, and a spouthead still exists bearing the date 1769 together with the crest and initials of Col. Mordaunt.

Change was in the air: the Colonel bored for coal in the Rectory garden - a process assisted by his brother Henry Mordaunt being Rector - and tapped a chalybeate spring. Rector Mordaunt rebuked his brother for his wild ways - ‘he enlivened Ormskirk with public sword practice’ - and the Colonel responded by making a bonfire out of green stuff and smoking brother and congregation out of the the Church.

But for other reasons, Halsall, still a sleepy backwater, would soon become famous.

The First Event

One of the major constraints on economic development in the eighteenth century was the appalling state of transportation. The roads alternated between mud baths and dust bowls, depending on the season, while navigable rivers were few and far between. Relatively small scale works, such as the Douglas Navigation between Wigan and the Ribble Estuary, had improved matters to some extent, but in 1767 two groups of far-sighted businessmen set up committees, one in Liverpool and one in Leeds, to investigate the construction of a canal to link the growing industrial areas with the coal fields and the major ports of the North East and North West of England. The outcome of their planning was the Leeds and Liverpool Canal Act of 1770, which authorised the construction of the first major canal in Great Britain. The route of this canal passed immediately adjacent to Halsall, and the very first sod turned, in the construction of this industrial miracle, was turned on 5th November 1770 by Col. Mordaunt himself.

In 2006 a stone statue of the 'Halsall Navvy' by sculptor Thompson Dagnall was unveiled adjacent to the canal in Halsall to commemorate this event.

The Second Event

In his story so far, Col. Mordaunt seems to have followed the typical career of a gentleman of means, but at some point, now uncertain, the Colonel seems to have taken up the trade of cotton spinning. Equally uncertain is whether there was already a mill at Halsall, or whether Col Mordaunt started from scratch, but start he certainly did. The first positive evidence we have is found in a letter which he wrote to the Secretary At War on 7th October 1779, at the time of the cotton riots in Lancashire, giving warning of a riotous mob forming at Halsall. A sergeant and fourteen soldiers were sent from Liverpool to maintain order, and presumably protect Halsall Mill.

Unlike many of his class, it seems as though Col. Mordaunt took more than a passing interest in the operation of his enterprise. A letter to the Society of Arts, written in 1780, refers to some development of the water wheel powering his mill:

'Having erected a considerable work by his majesty's Patent and being deficient in Water during the Summer Months, I thought of reworking the Water by the means enclosed, if it answers in operation, it will be an Acquisition of great consequence to Mechanics.'

It appears as though Col. Mordaunt believed he had achieved some kind of perpetual motion machine, and the paper was 'laid aside till further Notice.'

The reference to 'his majesty's Patent' concerned a patent which had been granted to Col. Mordaunt in 1778 for 'preparing cotton, sheep's wool, and flax; materials and necessary articles for manufacturing cotton and linen cloth.' Richard Arkwright's patents of 1769 and 1775 were still in force, and it seemed likely that some part of Col. Mordaunt's 'considerable work' might infringe Arkwright's rights. He certainly thought so, and as part of a programme of intended retribution against infringers of his patents, Arkwright launched a series of law suits in 1781 against ten mill owners whom he considered to be the principal culprits.

The Lancashire Ten decided that an attack on one was an attack on all, and agreed to mount a common defence. One of the Ten was Col. Mordaunt who, according to a leading Treasury Counsel of the time was 'a gentleman of family but not much fortune, who was thought from the lightness of his purse, the fittest to be put in the front.' Fortunately for Mordaunt, Arkwright lost the case, but because of the rather primitive nature of patent law at the time, did not lose his patents. This had to wait for a further trial in 1785 when the overthrow of the patent restrictions resulted in a massive expansion of mechanisation in the cotton industry. Arkwright's consolation was a knighthood, awarded in 1786.

The Third Event

By 1782, Col. Mordaunt could write to the Duke of Rutland:

'I am obliged for your enquiries after my health and our little work at Halsall. We have 600 spindles complete with their appendages - our powers calculated to 1,300 - an employment for about 160 poor children and women.'

By this time, the mill is recorded as being powered by an eighteen foot diameter overshot water wheel, fed by a stream. To anyone who examines the topography of Halsall today, it is quite difficult to understand quite how such a fall of water could ever have been achieved.

The relative scarcity of water, and the lack of height to provide a fall to drive the wheel, undoubtedly explain why, in 1782, Col. Mordaunt, through his Mill Superintendent John Moon, opened discussions with Boulton and Watt, of Soho, Birmingham, for the possible supply of a 'patent Fire Engine' which would be used either to pump water to operate the water wheel, or to operate the mill directly.

Whatever the irregularity of the water supply, it was nothing to the irregularity of the coinage. Effectively, no silver had been coined since 1758, and the Royal Mint had ceased production of copper in 1775. Increasing industrialisation meant an increasing burden for employers who required cash to pay their employees, and who were ever more unable to find sufficient quantities. There was no real shortage of money; there were local and Bank of England bank notes, and an adequate supply of gold coins. The real need was for small denominations which bore some relationship to the costs of living for mill workers. Worn-out discs of metal, forgeries and 'evasions' all became acceptable in the absence of anything better.

We will never know why, or when, the linkage occurred in Col. Mordaunt's mind, between his two perennial problems, water and cash, but there is no doubt that on 2nd December 1783, Superintendent John Moon wrote what has become one of the most significant letters in eighteenth century numismatics. It was addressed to Boulton and Watt:

Gentlemn.

We are frequently at a loss for Good Copper to pay the Hands employed under the Honrble Colonl Mordaunt at his Cotton Works now in a very flourishing state; His Honor order’d me this Day to write to you for a Die to Stamp Copper; The value of one, must be one Penny the other Two Pence; Or the weight of Four good Half Pence for the support in payment of the hands at his Works The Die with the Earl of Petersbourgh’s Coat of Arms on one side; And the word Halsall across the back. As you are coversant in Novels; I wish you to make (or procure made) the above mentioned Die for His Hons use; In this youl merrit the esteem of His Honr

For whom, I am yr most Obt Servt.

John Moon

Certainly the pennies exist, today, though there has never been any indication that two pences were ever produced.

Certainly the designs of the coins are precisely as set out in Mr Moon's letter. But in 1783, Matthew Boulton did not have a mint, as such, and whether he took the matter up, or whether he let it go to another manufacturer, we do not know. Boulton might have made the coins - he had been producing coin weights at Soho since 1775, and there is not that much difference between a coin and a coin weight - or possibly he made the dies and contracted the striking to someone else. The record is silent. And frustrating.

But whatever the source of the Halsall Penny, it seems likely that it pre-dates the enormous issue of penny tokens from the Parys Mine Company, in Anglesey, which started in 1787. The Halsall Penny is almost certainly the first of the flood of copper tokens which mark the great expansion of industry in the last decade or so of the eighteenth century.

Speculation, questions, but not many answers

But the Halsall Penny was not, of itself, a flood. Writing in 1908, in his 'Notes on Southport and District,' the Rev W T Bulpit described the Halsall tokens as 'now very valuable' but while the coins are not rare, neither do they appear in the bottom of junk boxes in street markets, as do the tokens of the Parys Mines and John Wilkinson.

Where was Col. Mordaunt's Mill? There should be an easy answer to a simple question such as this, but there isn't. The few local records which mention the mill seem to assume that everyone knew where it was! There are two possible sources of water. The photograph at left shows a watercourse running towards Halsall village, having passed underneath the Leeds and Liverpool canal. There are no signs on the surface of the ground in the village itself, and it has been suggested that the mill might have been in the basement cellars of the Hall itself. More likely is that the mill was in a separate building, in a field at the back of Halsall Hall itself, fed by the brook

When were the Halsall Pennies produced? There is no definite information; presumably some time after 2nd December 1783, and most probably before the advent of the Anglesey tokens in early 1787.

What purpose did they serve? R C Bell in his learned review of 'Commercial Coins' suggested that the Halsall tokens might have been estate passes, serving as admission tickets to the Mill and environs. The letter from Superintendent Moon surely disproves this theory. There can be little doubt that the pennies were intended to pay the workforce.

Where did they circulate? The area of their circulation is somewhat speculative, but in the Lancashire Record Office at Preston is a document headed 'State of the Copper Coins in Circulation at Liverpool, Anno 1791' which lists, in order and including the Halsall Penny, the best tokens to be found, but makes the note 'Mordaunt not in circulation.' Although disappointing, in that 'our' pennies were not in use, the document does indicate that they were well enough known in Liverpool for their absence to be something worthy of note. So it would seem reasonable to assume that they circulated generally in the area, and were not restricted to a factory 'truck' shop, as has been suggested.

Why did they go out of use? A possible reason for the decline in circulation centres on the weight of the tokens, and the reluctance of the people to accept light weight pieces. As long as Col. Mordaunt's pennies were unique, their weight of 25 pieces to the pound of copper would not matter; they were vastly better than anything else in circulation. When the Anglesey pennies arrived in 1787, their weight of 16 pieces to the pound would make them significantly more acceptable, and the Halsall pieces would meet with rejection.

The End?

There is no evidence that Col. Mordaunt repeated his experiment in coinage. Perhaps the ubiquitous tokens from Anglesey, and then slightly later, those issued by Iron Master John Wilkinson and the myriads of Liverpool Halfpennies ascribed to Thomas Clarke, made a second token unnecessary. But whatever did or did not happen later, to Colonel Charles Lewis Mordaunt belongs a significant place in the numismatic record.

The Colonel died in Ormskirk on 15th January 1808 aged seventy eight, and is possibly buried in the Parish Churchyard. The manor was sold to Thomas Eccleston Scarisbrick, of Scarisbrick, and the advowson to Jonathan Blundell, of Liverpool

Reviewing the history of the Halsall Penny today is fascinating, but is an exercise in frustration. There is just enough certain knowledge to whet the appetite, and enough knowledge missing to make much of the story speculative. But that is the nature of numismatics! But possibly, just possibly, they represent Matthew Boulton’s first tentative steps into coining.

Chris Leather

From: http://sohomint.info/tokenstory1.html

The first private tokens of the industrial revolution consisted of a modest issue of pennies from a small Lancashire village. Unfortunately little is known of these, just that they were made for Col Charles Mordaunt, who owned a mill, now vanished, in Halsall, near Southport. In the Birmingham City Archives, there is a letter from John Moon, Superintendent of the Halsall Mill, to Boulton, dated 2nd December 1783

His Honor order’d me this Day to write to you for a Die to Stamp Copper for the support in payment of the hands at his Works. The Die with the Earl of Petersbourgh’s Coat of Arms on one side; And the word HALSALL across the back As you are coversant in Novels; I wish you to make (or procure made) the above mentioned Die for His Hons use; In this youl merrit the esteem of His Honr

Were the dies made at Soho? Did Boulton strike the coins? We have no definite indication that Boulton took the job on, even though the tokens we see today closely match Mr Moon’s description. We think we know that Boulton did not have a mint until around 1789, which would suggest that the striking was done elsewhere, but we do know that he had been producing coin weights since at least 1775…. and in manufacturing terms there is little practical difference between a coin weight and a coin! But we don’t really know. As for its acceptability, a contemporary survey of tokens in circulation in Liverpool in 1791 reported that Col Mordaunt’s token was not found which, at least, suggests that it was well-enough known to have been expected.

From: http://www.numsoc.net/lancsct.html

The Eighteenth Century - I - Halsall and Lancaster By the beginning of the eighteenth century copper was well and truly established as the every day money of the poor. As the century progressed, new coppers were struck less and less often, until by 1775 production entirely ceased, just as the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of cash wages, put an increased demand on the copper coinage.

A survey by the Royal Mint in 1787 found that more than 90% of the coppers in circulation consisted of forgeries and evasions - coins which looked superficially like the real thing, but had meaningless inscriptions in order to avoid charges of forgery. In the face of governmental inertia, only one solution was possible. A second major round of vernacular token coinage began.

Precisely when is unclear. The best estimate is somewhere between the end of 1783 and around 1785. Where is quite clear. The 18th century answer to the cash shortage began at the cotton mill of Colonel Charles Mordaunt, in Halsall, near Southport.

There is a possibility that the dies for this issue were made by Matthew Boulton, but nothing is known for certain. By 1791, Colonel Mordaunt's pennies were reported as being no longer found in circulation in Liverpool. They had been supplanted by the Druid coins issued by the Parys Mine Company of Anglesey, and the Liverpool tokens of Thomas Clarke.

From: http://www.allertonoak.com/merseySights/OutlyingAreasLH.html

St. Cuthbert's Church, Halsall

Halsall was recorded in the Domesday Book, when it was one of the principal manors in the district. The village used to sit at the edge of a great moss that spread out to the west and became flooded in winter. Like much of the neighbouring area, the land has now been drained and is fertile crop growing territory. The church of St. Cuthbert dates from about 1320, probably replacing an earlier church, and stands on slightly higher ground, along with most of the older habitations. The 126 ft (38 m) tower and spire were added in about 1400, though the present spire is a more recent replacement. In mediaeval times, it appears that the area was leased to the Lord of Warrington, who extraordinarily enough paid 1 lb of cumin for the annual rent. I wonder if they had a curry house back then. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal passes behind the village and, indeed, the first excavations took place here in 1770. Halsall in Lewis's Topographical Dictionary of England (1848)

It is situated near the coast, and intersected by the Leeds and Liverpool canal, which passes through each of its townships; the views of the sea are good, and the air salubrious. There are some quarries of freestone; and in Halsall moss, which is rather extensive, is found a bituminous turf, which burns like a candle. The parochial church is handsome, partly in the decorated and partly in the later English style, with a lofty spire, and forms a conspicuous object in the scenery. Halsall in the Victoria History of the County of Lancaster (1907)

This township had formerly a great moss on the west, covering about half the surface, and constituting an effectual boundary. Down to recent times there were also three large meres - Black Otter, White Otter, and Gettern. The fenland has now been reclaimed and converted into fertile fields under a mixed cultivation - corn, root crops, fodder, and hay. There is some pasture land, and occasional osier beds fill up odd corners. The soil is loamy, with clay beneath. The low-lying ground is apt to become flooded after wet weather or in winter-time, and deep ditches are necessary to carry away superfluous water. In summer these ditches are filled with a luxuriant fenland flora, which thus finds shelter in an exposed country. The scanty trees show by their inclination the prevalence of winds from the west laden with salt. The ground rises gently to the east; until on the boundary 95 ft. is reached. [...]

The Liverpool, Southport, and Preston Junction Railway, now taken over by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Company, formed a branch through the township with a station called Halsall, half a mile west of the church, and another at Shirdley Hill. The scattered houses of the village stand on the higher ground near the church. To the south-east is the hamlet of Bangors Green; Four Lane Ends is to the north-east. From near the church an extensive and comprehensive view of the surrounding county is obtained. The northern arm of the Downholland Brook rises in and drains part of the district, running eventually into the River Alt, which is the natural receptacle for all the streams and ditches hereabouts. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal crosses the southeastern portion of the township, with the usual accompaniment of sett-laid roads and untidy wharfs. [...] The hall is to the south-west of the church; between them was a water-mill, taken down about 1880. North-east of the church are portions of the old rectory house, consisting of a wall 55 ft. long, with three doorways and three two-light windows, several traces of cross walls, and a turret at the north-west. Part is of fourteenth-century date.

From: http://www.lan-opc.org.uk/Halsall/index.html

Historically, the Parish of Halsall consisted of the villages of Halsall, Barton, Haskayne, Downholland, Lydiate and Maghull and the hamlets of Shirdley Hill and Bangor’s Green.

The parish is about 9 miles long and 4 miles wide and runs roughly north to south, with the market town of Ormskirk 3 miles to the east and the Irish Sea 5 miles to the west. Halsall Moss, an area of very fertile farmland reclaimed by drainage, occupies much of the western part.

The name Halsall comes from the Doomsday word Heleshale meaning “rising ground near the edge of the great bog or mire” but by 1212, the village was already referred to as Halsale.

The Parish Church of St Cuthbert dates from 1250 but has been rebuilt and embellished in the intervening years. It is regarded, by many, as one of the finest churches in the area.

The population and its environment were very much influenced by the advances made in transport during the Industrial Revolution. At one time the parish could boast a turnpike road, a canal and two railways.

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halsall

Halsall is a village and civil parish in West Lancashire, England, located close to Ormskirk on the A5147 and Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The parish has a population of 1,921 and covers an area of 28.31 square kilometres. The church and much of the village stand on a rocky ridge, in marked contrast to the low-lying flat peat mossland between the ridge and the sand of Ainsdale and Birkdale.

In Halsall there is St Cuthbert's Church, which dates from 1250 and is famed as the oldest Parish Church in England (although several reconstructions have taken place), the vicar of which is the Rev. Paul Robinson (also vicar of Lydiate). There is a junior school, St Cuthbert's Church of England Primary School with around 140 pupils from age 4 to 11. The Saracen's Head pub is a large public house on the banks of the canal. There is also a post office, a garage, a financial adviser office (in what used to be the Scarisbrick Arms public house) and a phone box. Halsall now has a pharmacy, situated by the playing fields. The central feature in the village is the war memorial located in front of the church on what is now a traffic island.

Halsall is where the first sod was ceremonially dug (on 5 November 1770, by the Hon Charles Mordaunt of Halsall Hall) for the commencement of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, and a sculpture ("Halsall Navvy" by Thompson Dagnall) just across the bridge from the Saracen's Head pub now commemorates this. Halsall Hall still stands, but it is now divided into several houses.

Halsall built up from being a small farming settlement, and, reflecting this background, a lot of the land area of Halsall is sparsely populated with many isolated dwellings. The land area (and postal area) of Halsall extends quite a way towards Ainsdale along Carr Moss Lane, to a point where the border is closer to Ainsdale village centre than it is to Halsall.

The village has two bus stops, served by the 300 bus route, operated by Arriva, travelling from Liverpool to Southport (and the reverse) and the 315 operated by Holmeswood Coaches, running between Southport and Ormskirk. Halsall railway station on the Liverpool, Southport and Preston Junction Railway was in service between 1887 and 1938.

From: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41318

The parish of Halsall is about ten miles in length, and has a total area of 16,698 acres, (fn. 1) of which a considerable portion is reclaimed mossland.

Judging by the situation of the various villages and hamlets it may be asserted that in this part of West Lancashire the 25 ft. level formed the boundary in ancient times of the habitable district. All below it was moss and swamp, which here formed a broad and definite division between Halsall parish on the east and Formby and Ainsdale on the west.

The parish used to contribute to the county lay as follows:—When the hundred paid £100, it paid a total of £6 5s. 0¼d., the townships giving—Halsall, £1 8s. 1½d.; Downholland, £1 5s. 9½d.; Lydiate, £1 5s. 9½d.; Maghull, 17s. 2¼d.; Melling, £1 8s. 1½d. To the more ancient fifteenth the contributions were: Halsall, £2 4s. 1½d.; Downholland, £1 12s.; Lydiate £1 8s. 8d.; Maghull, 12s.; and Melling, £1 13s. 4d. or £7 10s. 1½d. when the hundred paid £106 9s. 6d. (fn. 2)

Before the Conquest the whole of the parish, with the exception of Maghull, was in the privileged district of three hides. Soon after 1100 the barony of Warrington included the northern portion of the parish, Halsall, Barton, and Lydiate; while Maghull was part of the Widnes fee, and Downholland and Melling were held in thegnage.

The history of the parish is uneventful. During the religious changes of the Tudor period, Halsall is said to have been the last parish to adopt the new services. This, of course, cannot be proved; but the immediate reduction of the staff of clergy, the partial or total closing of the chapels at Maghull and Melling, and the careful dismantling of that at Lydiate, are tokens of the feeling the changes inspired.

The freeholders in 1600 were Sir Cuthbert Halsall of Halsall, who was a justice of the peace; Lawrence Ireland of Lydiate, Lydiate of Lydiate, Richard Molyneux of Cunscough, Richard Hulme of Maghull, Richard Maghull of Maghull, Robert Pooley of Melling, Robert Bootle of Melling, Gilbert Halsall of Barton, Henry Heskin of Downholland. (fn. 3) In the subsidy list of 1628, the following landowners were recorded:—At Halsall, Sir Charles Gerard and Mr. Cole; Downholland, Edward Haskayne and John Moore; Lydiate, Edward Ireland and Thomas Lydiate; Maghull, Richard Maghull; Melling, Robert Molyneux, Robert Bootle, Lawrence Hulme, the heir of William Martin, Anne Stopford, widow, and the heirs of John Seacome. (fn. 4) George Marshall of Halsall, Edward Ireland, and Robert Molyneux paid £10 each in 1631 on refusing knighthood. (fn. 5)

The recusant and non-communicant roll of 1641 names five distinct households in Halsall; large numbers in Downholland and Lydiate; several at Maghull, and at Melling. (fn. 6)

During the Civil War there is little to show how the people of the district were divided. The principal manorial lord, Sir Charles Gerard of Halsall, was a Protestant but a strong Royalist; he probably did not live much in the place. His son and successor was an exile. Ireland of Lydiate was a minor; Maghull was in the hands of Lord Molyneux, a Royalist; and Robert Molyneux of Melling was on the same side. The Gerard manors were of course sequestered by the Parliament, and in 1653 orders were given to settle a portion of them, of the value of £600 a year, upon the widow and children of Richard Deane, later a general of the fleet. (fn. 7) Radcliffe Gerard, brother of the late Sir Charles, described as 'of Barton,' petitioned for delay in paying his composition because his annuity had not been paid for twelve years past. (fn. 8) John Wignall, of Halsall, was allowed to compound in 1652. (fn. 9)

The troubles of the Irelands are narrated under Lydiate; the estate of Edward Gore there was sequestered and part sold. (fn. 10) Confiscations at Maghull and Melling are related in the account of these townships; in the former place also Richard Mercer, a tailor, had had his estate seized for his 'pretended delinquency,' but it had never been sequestered and he obtained it back. (fn. 11)

The hearth tax of 1666 shows that very few houses in the parish had three hearths. In Downholland the Haskaynes' house had seven hearths and the hall five. In Lydiate the hall had ten; in Maghull James Smith's had nine and Richard Maghull's six; in Melling Robert Molyneux's house had ten hearths, William Martin's six, Thomas Bootle's five, and John Tatlock's, in Cunscough, eight. (fn. 12)

The connexion of Anderton of Lydiate with the Jacobite rising of 1715 seems to be isolated; the squires and people generally took no share in this or the subsequent rising of 1745.

The land tax returns of 1794 show that, except in Lydiate, the land was in the possession of a large number of freeholders.

The making of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at the end of the eighteenth century did something to open up the district, which has, however, remained almost wholly agricultural.

The geological formation consists entirely of the new red sandstone, or triassic, series. Taking the various beds in rotation from the lowest upwards, the pebble beds of the bunter series occur to the eastward of the canal in Melling, and to the south of a line drawn from Maghull manor-house to the nearest point on the boundary of Simonswood. To the east of a line drawn southward from Halsall village to pass a quarter of a mile or so to the eastward of the villages of Lydiate and Maghull, following the line of a fault, the upper mottled sandstones of the same series occur, whilst to the west of the same line the formation consists of the lower keuper sandstones. To the north-west of a line drawn from Barton and Halsall station to Scarisbrick bridge, spanning the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, the keuper marls occur, whilst the waterstones, which elsewhere intervene between these two members of the keuper series, are entirely wanting.

There are stone quarries at Melling and Maghull, producing good grindstones. About 1840 some of the inhabitants were employed in hand - loom weaving. (fn. 13) The agricultural land is occupied as follows: Arable, 13,337 acres; permanent grass, 1,515; woods and plantations, 10.

CHURCHThe church of St. Cuthbert consists of a chancel with north vestry and organ chamber, nave with north and south aisles and south porch, west tower and spire, and to the south of the tower a late sixteenth-century building, formerly a grammar school. It stands finely on rising ground on the edge of the broad stretch of level land which once was Halsall Moss, and is, as it must have been designed to be, a conspicuous landmark for miles round. Two roads join at the west end of the churchyard, from which point a raised causeway runs across a depression in the ground in which is a little stream flowing northward, and joins the outcrop of sandstone rock, facing the church, on which the hall and part of the village stand.

No part of the church as it exists to-day is older than the fourteenth century, and its architectural history seems to be as follows. The nave with north and south aisles and south porch were begun about 1320, doubtless replacing the nave of an older building, whose eastern portions were left standing till 1345–50, when they were destroyed and the present fine and stately chancel built. The work seems to have gone on continuously, but there were several alterations of the first design, which will be noticed in their place. When the new chancel was complete— it was no doubt built round the old chancel after the usual mediaeval fashion, beginning at the east—it is quite clear that the intention of the builders was to go on and re-model the nave, if not to rebuild it, although it was barely thirty years old at the time. But the work came to a sudden stop when the east wall of the south aisle was being built, and nothing more was done to the fabric for some fifty or sixty years, when the west tower and spire were added, and the church assumed substantially its present appearance. About 1520 a large three-light rood window was inserted high up in the south wall of the nave, and in 1593 Edward Halsall's grammar school was built at the west end of the south aisle. The north and south aisles were nearly rebuilt in 1751 and 1824, and in 1886 the north wall of the north aisle and vestry was rebuilt throughout its length, as was the greater part of the south aisle wall, with the south porch and doorway, though both this doorway and the outer arch of the porch have been reconstructed with the old stones as far as they would serve.

Remains of mediaeval arrangements are plentiful. In the chancel are triple sedilia and a piscina, a large piscina and a locker in the vestry, and there are piscinae at the eastern ends of both nave aisles. Traces of the roodloft are to be seen, and the roodstair remains perfect, but the nave altars below the loft have left no trace. The patron saint's canopied niche exists on the north of the altar, and in the north wall of the chancel is a fine sepulchral recess which was doubtless made use of in Holy Week for the purposes of the Easter Sepulchre. A wood screen on a low stone wall stood in the chancel arch, and against it the stalls were returned. Some of these stalls, of the fifteenth century, still remain, but the return stalls, for which evidence was found some years ago, have disappeared. A turret for the sanctus bell stands on the east gable of the nave.

The architectural details of the chancel are exceedingly good, and in common with the rest of the church it is faced with wrought stone both inside and out. Its internal dimensions are 47 ft. long by 20 ft. 6 in. wide, and it is 46 ft. high to the ridge of the roof. It is divided into three bays, having three-light windows in each bay on the south side, and a five-light east window. There are no windows in the north wall. The stone used is a sandstone of local origin, but of a quality very superior to the ordinary. The jambs and heads of the windows are elaborately moulded, internally with the characteristic roll and fillet, and hollow quarter-round; while externally the orders are square, each face being countersunk, the effect being to leave a raised fillet at the salient and re-entering angles. This detail also occurs on the east window of the south aisle. The tracery of the east window is mainly original, and that of the south windows a modern copy of the former work; it is very late in the style, and shows a distinct tendency to the characteristic upright light of the succeeding style. Above the head of the east window, inside, is a hand carved in low relief, somewhat difficult to see from below. It is said by those who have seen it at close range to be an insertion.

The sedilia, in common with nearly all the masonry details of the chancel, are original. They are triple, with cinquefoil arches and moulded labels which mitre with the string running round the chancel walls. The three seats are on the same level, and the piscina forms a part of the composition, being under an arch similar to the other three, and adjoining them to the east. Its bowl is elaborate, with a cusped sinking of some depth, but the drain is not visible, though the bowl seems to be part of the original masonry. It projects from the wall, and is carved on the underside with foliage and a small mitred figure. The niche north of the altar, which probably held St. Cuthbert's image as patron saint, has a fine crocketed canopy, with flanking pinnacles and a central spirelet and finial. The corbel to carry the figure projects as three sides of an octagon, and is carved below with oak foliage and acorns. The image itself was bonded into the back of the recess at half height, and the head dowelled to the wall. On either side of the shafts of the pinnacles which flank the niche are two pin-holes, probably for the fastenings of iron rods.

The first ten feet of the north wall, from the east, are blank, but about opposite to the sedilia is a recess 6 ft. 6 in. wide, and 14 in. deep, under a beautiful feather-cusped arch set in a crocketed gable and flanked by tall crocketed pinnacles; the pinnacles and gable finish at the same level, about 17 ft. from the floor, with heavy and deeply-cut finials of foliage, whose flattened tops seem designed to serve as brackets for images. It is to be noted that the arch is not constructive, but all joints are horizontal and part of the walling. In the recess is a plain panelled altar tomb, on which lies an ecclesiastical effigy of alabaster, wearing a fur almuce with long pendants over an alb and cassock; the head rests on a cushion, on either side of which are small winged figures, and at the feet is a dog. The effigy is of much later date than the recess, and both effigy and recess have been injured by a process of adaptation, the back of the recess being hollowed out, and the head and feet of the effigy cut back to get them to fit the space. The effigy is not later than 1520. A tomb in this position in the north wall of the chancel was often used as the place of setting up the Easter Sepulchre, and adjoining the recess to the west is a curious masonry projection, splayed off at a height of 2 ft., and dying into the wall face at 3 ft. 9 in. from the floor. It is 4 ft. 8 in. long, with a maximum projection of 12 in. There are no traces of fastenings or dowel-holes on it (in which case it might have formed a backing for the wooden framework of the sepulchre), and its purpose is hard to understand. It is of the same date as the recess, for the stooling of the western flanking pinnacle is worked on one stone of its sloping top, and the masonry joints range with the surrounding walling. Close to it on the west is the vestry doorway, of three orders with continuous mouldings and a hood mould formed by carrying the chancel string round the arch, an admirable piece of detail, retaining its original panelled door, with reticulated tracery in the head, and lock and handle of the same date. To the west of this doorway is a modern arch for the organ. The chancel arch is of three orders with engaged shafts, moulded capitals and bases, and a well-moulded arch with labels. It is 26 ft. high to the crown, and 15 ft. 8 in. to the springing. The central shaft shows the almost obliterated traces of the coping of a dwarf stone wall 10 in. thick, and about 3 ft. high, which served as a base to a wood screen across the arch; a 3 in. fillet on the central shaft has been cut away for the fitting of this screen.

Parts of the stalls are ancient, good and deeply-cut work of the end of the fifteenth century. They were re-arranged at the late restoration, and there are now six ancient stalls on the south side, and one on the north. All these retain their ancient carved seats, the subjects of the carvings being (1) wrestlers backed by two 'religious'; (2) an angel with a key in each hand, and wearing a cap with a cross; (3) a bearded head; (4) a flying eagle; (5) a fox and goose; (6) an angel with a book, wearing a cap with a cross; (7) fighting dragons. Some of the old desks remain, with boldly carved fronts and standards, the finials being a good deal broken; one of them has the Stanley eagle and child, another a lion standing. East of the southern stalls is an altar tomb with panelled sides containing shields in quatrefoils, which have lost their painted heraldry, and an embattled cornice. On the tomb lie two effigies, said to be those of Sir Henry Halsall, 1523, and his wife Margaret (Stanley). Besides the tombs already noticed there are a fragment of a brass to Henry Halsall of Halsall, 1589, memorials of the Brownells, Glover Moore, and others. (fn. 14)

The vestry on the north of the chancel was probably built in the first instance for its present purpose. Its north wall has been rebuilt, but the south and east walls show some very interesting features. The south wall, which is also, of course, the north wall of the chancel, was originally designed as an outer wall, and had a plinth like that of the rest of the chancel; but when the wall had been built to the level of the top of the plinth the design was altered and the vestry built as it now is, the plinth being cut away, leaving its profile in the east wall. A large piscina was placed in the south wall, and the east wall built against the west side of the second buttress from the east, with a locker at the south end and a central window of one wide, single cinquefoiled light with a trefoil in the head. This window is somewhat clumsy, and shows signs of having been rebuilt. It does not belong to the chancel work, but its details are those of the nave, and it is probably an adaptation of the east window of the north aisle of the nave. Under the first design for the chancel this window would not have been disturbed, but when the vestry was added to the east it became useless, and was probably taken down and rebuilt in an altered form in its present place. (fn. 15) The two rows of corbels in the south wall of the vestry show the line of former plates, belonging to a roof now gone.

Externally the chancel has a fine moulded plinth of two stages and a string at the level of the window sills. The buttresses set back 3 ft. above the string with weathered and crocketed gablets, with excellent details of finials and grotesque masks, and are carried up through a simple parapet projecting on a corbel course to crocketed pinnacles, which have at their bases boldly designed gargoyles, the most noteworthy being that at the south end of the east face of the chancel, a boat containing a little figure with hands in prayer. In the east gable, above the great east window, is a single trefoiled light which lights the space over the chancel roof. The roof is of steep pitch, covered with lead; the timbers are mainly ancient, and are simple couples with arched braces under a collar. At the western angles of the chancel are square turrets finished with octagonal arcaded caps and crocketed spirelets. The southern turret contains the rood stair, which is continued upwards to give access to the nave and chancel gutters on both sides of the roof in an original and interesting manner. The northern turret contains no stair from the ground level, and appears never to have done so, being built solid at the bottom. It could not therefore give access to the northern gutters or roof-slopes; and this was provided by taking a passage from the south turret over the chancel arch in the thickness of the wall, opening into the north turret in its octagonal story, whence doors east and west led to the gutters. The passage rises at a steep pitch from both ends, and is lighted by four small square-headed loops, two towards the nave and two towards the chancel. (fn. 16) On the apex of the gable above is an octagonal sanctus bell-cote with a crocketed spirelet, which is open to the passage, and it is quite possible that the bell may have been rung from here at the elevation, as anyone standing at the loops looking towards the chancel has a clear view of the altar. Access to the west end of the chancel roof is also obtained from the highest point of the passage, and in the west wall at this point, exactly over the apex of the chancel arch, is a short iron bar, which may be connected with the fastenings of the rood.

The nave is of four bays with north and south arcades having octagonal bases, shafts, and capitals, 11 ft. 6 in. to the spring of the arches, which are of two orders with the characteristic fourteenth-century wave-moulding. There is no clearstory, and the whole work is much plainer and simpler than that of the chancel. The nave roof is 47 ft. high to the ridge, covered with stone healing, and the timbers are modern copies of the old work. At the east end of the nave the junction of the two dates of work is clearly shown in the masonry of both walls, and the plate level of the later work is considerably higher than that of the nave. On the south side the upper part of the wall has been cut away for the insertion of a three-light sixteenth-century window with square head, embattled on the outside, its object, as already mentioned, being to light the rood and rood-loft. There are many traces of the beams which carried the rood-loft, which was entered from the south turret by a still existing doorway. Access to the turret is from the south aisle, the lower part of its stone newel being treated as a shaft with moulded capital and base. About ten feet up the stair is lighted by three narrow loops at the same level, one on the south, looking out on the churchyard, one on the north-east, commanding the tomb in the north wall of the chancel, and one on the north-west, towards the nave, below the level of the rood-loft floor. From the north-east loop nothing but the tomb in the north wall can be seen, and it is evidently built for that object only. It was in all probability used for watching the Easter Sepulchre erected over the tomb. Anyone standing here could also command the entrance of the chancel from the nave and the south-east portion of the churchyard.

The south aisle of the nave has been largely rebuilt, but retains a piscina in the east end of its south wall. At the foot of the east wall a course of masonry of 3 in. projection runs southward from the angle by the turret doorway for 6 ft. 3 in., and its reason is not apparent, but it may show that the floor level here was originally higher, and it is further to be noted that this would go some way towards accounting for the curious fact that the base of the south nave respond is a foot higher than that of the north. (fn. 17) The east wall with its window and angle buttresses are of the chancel date, agreeing exactly in detail with the south windows of the chancel. There is a little ancient glass, some of it of original date, in this window. It is chiefly made up of fragments collected from other places, but the two angels in the tracery seem designed for their position. Owing to the projection of the stair turret the window is thrown considerably out of centre, and the roof timbers barely clear its head. It is conceivable that a gabled roof was contemplated in the projected rebuilding, which came to a sudden stop at this point. It naturally occurs to the mind that a stoppage of work on a building of this date, circa 1350, may be a result of the Black Death of 1348–9, which has left so many traces of its severity all over the country. The south doorway and porch entrance, mentioned above as partly rebuilt with the old masonry, are alike in detail, of three orders with wave moulding. Over the outer entrance is a modern niche with a figure of St. Cuthbert.

In the north aisle nothing ancient remains but the west wall and window of two lights with fourteenthcentury tracery and jambs and head with wave moulding. A little old glass is set in the window, a piece of vine-leaf border being of fourteenth-century date. The west face of this wall shows a straight joint, partly bonded across, on the line of the north arcade wall, which tells of a stage in the building of the nave when its west wall was built, but not that of the aisle. In this case it seems doubtful, as the masonry is so alike in both parts, whether the angle is much earlier than the aisle wall and represents an aisleless nave. The evidence at the corresponding western angle is destroyed.

Externally the nave has little of interest to show; the main roof has a plain parapet, much patched at various dates. On the north side is a tablet with churchwardens' names of 1700, (fn. 18) and another on the south, with the date illegible, but of much the same time. (fn. 19) The modern aisle-windows are good of their kind, square-headed, with tracery of fourteenthcentury style.

The west tower is 126 ft. high, of three stages with a stone spire, which is modern, replacing an old spire of somewhat different outline. The octagonal parapet at its base is also modern, with the four gargoyles representing the evangelistic symbols. They replace four ancient gargoyles in the shape of nondescript monsters, now to be seen set up among the ruins of the fourteenth-century building northeast of the church. The top of the parapet is 63 ft. from the ground. The tower is of the first half of the fifteenth century; whether the church had a tower before this time does not appear, but the foundations of the west wall of the nave are said to run across the tower arch, and there must have been a western wall of some sort, temporary or otherwise, before the building of the present tower, unless perhaps an older tower was preserved at the rebuilding of the nave. The design is that of the Aughton and Ormskirk towers, with square base and octagonal belfry and spire. In the belfry stage are four squareheaded two-light windows, with a quatrefoil in the head; the second stage contains the ringing floor, and forms the transition from octagon to square. The lowest stage has a two-light square-headed west window and boldly projecting corner buttresses, with raking gabled sets-off reminiscent of the chancel buttresses. In the head of the northern of the two western buttresses is a small roughly cut sinking which may have held a small figure. The tower stair is in the south-west angle, entered from within through a low angle doorway with jambs having the common fifteenth-century double ogee moulding; the stones of the jambs are marked with Roman numerals for the guidance of the masons in placing them. The tower arch of three orders is 26 ft. 4 in. high, with an engaged shaft on the inner order and continuous mouldings on the two outer, the detail being very good. Part of the walling above it may be of the nave date, and consequently a remnant of the former west wall.

The font has a circular basin panelled with quatrefoils on a circular fluted stem, which is the only ancient part, and appears to be of the early part of the fourteenth century. In the churchyard are several mediaeval grave slabs, turned out of the church during restoration; it would be a very desirable thing to bring them under cover, even if replacing in the nave floor is impossible. The octagonal panelled base of a churchyard cross is also to be seen, and the churchyard wall is of some age, probably sixteenth century, having a good deal of its old coping remaining. There is a picturesque sun-dial of 1725 with a baluster stem. Of wall paintings the church has no trace, except for a few remains of Elizabethan black-letter texts; and the piece of panelling with the Ireland arms and date 1627, at the east end of the south aisle, is the only old woodwork in the church, except part of the stalls and the chancel roof already described.

It remains to notice the gabled building running north and south, built into the angle of the tower and south aisle. It was built to contain a grammar school founded by Edward Halsall in 1593, and was originally of two stories, the main entrance being the now blocked doorway in the east wall, above which are the Halsall arms with 'E. H. 1593.' The west doorway, which is cut through the tower buttress, gave access to the stairs to the upper room, and the marks of their fitting remain in the tower plinth. Over this doorway are two panels, the upper having the Halsall arms and 'E. H. 1593,' and the lower a now illegible inscription, the words of which have fortunately been preserved:--

ISTIUS EXSTRUCTAE CUM QUADAM DOTE PERENNI EDWARDO HALSALLO LAUS TRIBUENDA SCHOLAE.

The windows, of which there are two on the west and one on the south, are of two lights with arched heads, churchwarden gothic of the poorest, inserted after the removal of the upper floor. A fireplace remains at both levels, and in the east wall is a modern doorway into the south aisle.

There are six bells, four recast in 1786, one cast in 1811, and another in 1887. The curfew bell is rung in the winter months. (fn. 20)

The church plate consists of several plain and massive pieces, all made in London, viz.: a chalice and paten, 1609; chalice and paten, 1641; flagon and paten, 1730; two small chalices, 1740. (fn. 21)

The register of baptisms begins in 1606, that of marriages and burials in 1609; but they are irregularly kept until 1662. From this time they seem to be perfect. (fn. 22)

ADVOWSONFrom the dedication of the church (fn. 23) it has been supposed that Halsall was one of the resting-places of St. Cuthbert's body during its seven years' wandering whilst the Danes were ravaging Northumbria (875– 83). The words of Simeon of Durham are wide enough to cover this: the bearers 'wandered over all the districts of the Northumbrians, with never any fixed resting-place'; but the places he names—the mouth of the Derwent, Whitherne, and Craik (Creca) —point to Cumberland and Galloway rather than to Lancashire. (fn. 24)

The patronage, like the manor, was in dispute in the early years of Edward I between Robert de Vilers and Gilbert de Halsall, (fn. 25) but the latter seems to have vindicated his right, as his descendants continued to present down to the sale of the manor to the Gerards, when the advowson passed with it. In 1719 and 1730 Peter Walter, a 'usurer' denounced by Pope, presented; (fn. 26) and about 1800 the lord of the manor sold the advowson to Jonathan Blundell, of Liverpool, whose descendant, the late Colonel H. Blundell-Hollinshead-Blundell, was patron.

The Taxatio of 1291 gives the value of Halsall as £10. (fn. 27) The Valor of Henry VIII places it at £28 10s. (fn. 28) The rectors have from time to time had numerous disputes as to tithes and other church property. Rector Henry de Lea complained that in 1313 the lord of the manor had seized his cart and horses owing to a disputed right of digging turf. (fn. 29) A later rector, about 1520, leased the tithes of the township of Halsall to his brother Thomas Halsall, the lord of the manor, for 14 marks yearly. But seven years later he had to complain that Thomas would not pay the tithe-rent, and that he had refused the rector's tenants the common of pasture on Hall green, and common of turbary, which had been customary. (fn. 30)

Bishop Gastrell in 1717 found the rectory worth £300 per annum, Lady Mohun being patron. There were two churchwardens, one chosen by the rector and serving for Halsall township, the other by the lord of the manor and serving for Downholland. (fn. 31) From this time onward the value of the rectory increased rapidly. (fn. 32) The gross value is now over £2,100.

Halsall has obviously been regarded as a 'family living' from early times, as witness the promotion of mere boys to the rectory because they were relatives of the patron.

Master Richard Halsall, a younger son of Sir Henry Halsall, was rector for fifty years, from 1513 to 1563, seeing all the changes of the Tudor period. (fn. 60) In 1541–2, besides the rector and the two chantry priests there were attached to Halsall parish three clergy, two paid by the rector, and perhaps serving the chapels of Melling and Maghull, and one paid by James Halsall. (fn. 61) In 1548 there was much the same staff, six names being given, though 'mortuus' is marked by the bishop's registrar against one. (fn. 62) In 1562 the rector appeared at the visitation by proxy (fn. 63) —probably he was too infirm to come. John Prescott the curate came in person; the third resident priest died about the same time. In 1563 the new rector was absent at Oxford; Prescott was still curate, but was ill—subsequently 'defunctus' was written against his name. Two years later Master Cuthbert Halsall (fn. 64) appeared by proxy, and the curate was too ill to come. (fn. 65) It would thus appear that the pre-Reformation staff of six—not a large one for the parish—had been reduced to an absentee rector and a curate 'indisposed' at the visitation. (fn. 66) George Hesketh, (fn. 67) the next rector, was in 1590 described as 'no preacher.' (fn. 68) The value of the rectory was £200, but the parson, 'by corruption,' had but £30 of it. (fn. 69) His successor, Richard Halsall, was in 1610 described as 'a preacher.' (fn. 70)

On the ejection of the Royalist Peter Travers or Travis about 1645 Nathaniel Jackson was placed in charge of Halsall. He soon relinquished it, and in December, 1645, 'Thomas Johnson, late of Rochdale, a godly and orthodox divine,' was required to officiate there forthwith and preach diligently to the parishioners; paying to Dorothy Travers a tenth part of the tithes for the maintenance of her and her children. (fn. 71) On 23 August, 1654, a formal presentation to Halsall was exhibited by Mary Deane, widow of MajorGeneral Richard Deane, the true patroness; she of course nominated Thomas Johnson. (fn. 72) He, as also William Aspinall of Maghull and John Mallinson of Melling, joined in the 'Harmonous Consent' of 1648. The Commonwealth surveyors of 1650 approved him as 'an able minister.' (fn. 73) Thomas Johnson stayed at Halsall until his death at the end of 1660. (fn. 74)

The later rectors do not call for any special comment.

Mention of a minor church officer, Robert Breckale, the holy-water clerk, occurs in 1442. (fn. 75)

There were two chantries. The first was founded by Sir Henry Halsall, for a priest to celebrate for the souls of himself and his ancestors; a yearly obit to be made by the chantry priest, and a taper of two pounds' weight to be kept before the Trinity. This was at the altar of Our Lady, and Thomas Norris was celebrating there at the time of the confiscation. There was no plate, and the rental amounted to £4 4s. 5d. (fn. 76)

A second chantry was founded about 1520 by the same Sir Henry Halsall in conjunction with Henry Molyneux, priest, (fn. 77) for a commemoration of their souls. This was at the altar of St. Nicholas, and in 1547 Henry Halsall was celebrating there according to his foundation. There was no plate, and the rental amounted to no more than 64s. 4d. (fn. 78) The chantry priest was aged fifty-six in 1548; the full stipend was paid to him as a pension in 1553. He died in 1561 or 1562, and was buried at Halsall. (fn. 79)

A free grammar school was established here in 1593 by Edward Halsall, life tenant of the family estates.

CHARITIESApart from schools (fn. 80) and the benefaction of John Goore to Lydiate, the income of this amounting now to £136 a year, (fn. 81) the charities of Halsall are inconsiderable, (fn. 82) and are restricted to separate townships. (fn. 83)

Footnotes 1 16,682 acres, according to the census of 1901; this includes 87 acres of inland water. 2 Gregson, Fragments (ed. Harland), 22, 18. 3 Misc. (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), i, 238–43. 4 Norris D. (B.M.). The only 'convicted' recusant, charged double, was Edward Ireland. 5 Misc. (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), i, 213. 6 Trans. Hist. Soc. (New Ser.), xiv, 232. 7 Royalist Comp. P. (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), iii, 6–18. 8 Ibid. iii, 23. His delinquency was being in arms against the Parliament; he had laid them down in 1645 and taken the National Covenant and the Negative Oath. 9 Cal. Com. for Comp. iv, 2953; he had been in arms for the king in the first war. 10 Royalist Comp. P. iii, 87. 11 Ibid. iv, 130. 12 Lay Subs. Lancs. 250–9. 13 Lewis, Gazetteer. 14 A full description of the church and its monuments with plates is given in Trans. Hist. Soc. (New Ser.), xii, 193, 215, &c.; for the font, ibid. xvii, 63. A view is given in Gregson's Fragments (ed. Harland), 215. See also Lancs. Churcbes (Chet. Soc.), 106, for its condition in 1845. 15 That the change of design took place at a very early stage of the building is clear for three reasons: (i) that the piscina in the south wall is of the same masonry as the wall, i.e. it is not a subsequent insertion; (ii) that the vestry doorway is built from the first to open into a building and not to the open air (it would, of course, have been reversed if this had been the case); (iii) that the buttress west of the doorway, although having the gabled weathering of the other external buttresses, has never had a plinth; the vestry door could not open if it had. 16 There is a similar arrangement at Wrotham church, Kent. 17 The position is a normal one for a charnel, beneath the east end of the aisle, and the floor level might well be raised on this account. 18 The inscription reads:--

IOHN · SEGAR

HENRY · YATE

CHURCHWARD ·

N. B. R. 1700.

i.e. Nathaniel Brownell, Rector. 19 The inscription is:--

RICHARD HES

KETH ROBERT

MAUDESLEY

CHURCHWAR

DENS ///////// 20 Trans. Hist. Soc. (New Ser.), xii, 224, 231. 21 Ibid. 22 Ibid. p. 230. 23 In a charter dated 1191 Mabel daughter of William Gernet granted an acre of land in Maghull, to God and St. Cuthbert of Halsall. Dods. MSS. xxxix, fol. 142b. 24 Sim. Dunelm. (Rolls Ser.), i, 61–9. The later wandering (995) seems to have come no nearer Halsall than Ripon; ibid. i, 78, 79. 25 De Banc. R. 10, m. 55; 11, m. 109. 26 Peter Walter, money scrivener and clerk to the Middlesex justices, died in 1746, aged 83, leaving a fortune of £300,000 to his grandson Peter Walter, then M.P. for Shaftesbury; Lond. Mag. 1746, p. 50; Herald and Gen. viii, 1–4. 27 Pope Nich. Tax. (Rec. Com.), p. 249. The ninth of the sheaves, &c., in 1341 was valued at 19 marks; Halsall, 84s. 5d.; the moiety of Snape, 6s. 5d.; Downholland, 32s.; Lydiate, 50s. 8d.; Maghull, 29s. 2d.; and Melling, 50s. 8d. Inq. Nonarum (Rec. Com.), 40. 28 Valor Eccl. (Rec. Com.), v, 224. The sum was made up of assized rents of lands belonging to the church, 32s. 8d.; tithes, £21 10s. 8d.; oblations and Easter roll, £5 6s. 8d. The fee of James Halsall, the rector's bailiff, was 66s. 8d., and synodals and procurations to the archdeacon, 12s. 29 De Banc. R. 211, m. 94. It is noticeable that the rector asserted that a quarter of the manor belonged to the rectory, only three-quarters being held by Robert de Halsall. The latter, however, claimed the whole, including the portion of waste in Forth Green, near the High Street (regia strata), as to which the dispute arose. In 1354 Richard de Halsall, rector, claimed common of turbary belonging to five messuages and five oxgangs in Halsall, in right of the church; this was allowed, in spite of the opposition of Otes de Halsall and Robert de Meols; Duchy of Lanc. Assize R. 3, m. ij. 30 Duchy of Lanc. Pleadings, Hen. VIII, v, H. 8. 31 Notitia Cestr. (Chet. Soc.), ii, 172. It was the custom to tithe the eleventh cock of hay and hattock of corn. 32 Matthew Gregson, about a hundred years later, stated that 'the late Rector Moore never received for his tithes more than £1,400 per annum,' though the rental of the parish was given as nearly £25,000; Fragments, 215. 33 A witness; Dods. MSS. xxxix, fol. 143 (64); Cockersand Chartul. (Chet. Soc.), ii, 572, 754. Also about 1230 'Robert parson of Halsall, Roger his brother'; Trans. Hist. Soc. xxxii, 186. 34 Cockersand Chartul. ii, 602. 35 Dods. MSS. xxxix, fol. 138; Assize R. 408, m. 56 d. 36 Lich. Epis. Reg. i, fol. 27; also fol. 28, two years' leave of absence for study, Jan. 1307–8; fol. 103, Henry de Lea, rector of Halsall, ordained subdeacon Dec. 1306 (?); fol. 106, priest, Sept. 1308. He was probably the Henry son of Henry de Lea, clerk, who was concerned with Down Litherland; Final Conc. (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), ii, 27; for Henry de Lea, rector of Halsall, was in 1333 witness to a Litherland charter; Moore D. n. 717. 37 Lich. Reg. i, fol. 111; called 'son of Thomas de Halsall.' He was ordained subdeacon Sept. 1337, fol. 183. He was still living in 1354; Duchy of Lanc. Assize R. 3, m. ij. 38 Lich. Epis. Reg. iv. He was made a notary by Innocent VI in 1353; Cal. Pap. Letters, iii, 490. 39 Lich. Epis. Reg. vi, fol. 60b; he was in minor orders and nineteen years of age; vi, fol. 155b, ordained subdeacon Sept. 1396. He became archdeacon of Chester; Ormerod, Ches. i, 114. 40 Lich. Reg. vii, fol. 103b. W. Neuhagh was also a prebendary of Lichfield; he probably died in 1426, when his prebend became vacant; Le Neve, Fasti. He had been archdeacon of Chester since 1390, so that his appointment to Halsall was in the nature of an exchange with Henry Halsall. 41 Mentioned as rector in a plea of 1429; Pal. of Lanc. Plea R. 2; Scarisbrick Charter, 165. In 1425 Gilbert de Halsall, aged about twenty, obtained a papal dispensation enabling him to hold any benefice on attaining his twentysecond year; Cal. Papal Letters, vii, 390. 42 Lich. Epis. Reg. xi, fol. 3b. He was ordained subdeacon 24 Feb., fol. 5; deacon in May, fol. 97; and priest in Sept. 1453, fol. 98b. 43 Ibid. xii, fol. 158; ordained subdeacon in Sept. 1497, fol. 265; deacon in Dec. 1497, fol. 267b; and priest in Dec. 1500, xiii-xiv, fol. 289. Hugh Halsall was on institution obliged to take oath that he would pay a yearly pension of £20 for five years to James Straitbarrel, chaplain, of Halsall, and £13 6s. 8d. afterwards for life. There had been a dispute as to the patronage, Straitbarrel having been presented by Nicholas Gartside, patron for that turn; Lich. Epis. Reg. xii, fol. 158. In June, 1502, the archdeacon of Chester granted a dispensation to Hugh Halsall to retain his benefice, in spite of his having been instituted without dispensation before he was of lawful age (namely, in his nineteenth year), and ordained priest also before the lawful age; xiii, fol. 249b. 44 Ibid. xiii-xiv, fol. 58b. Richard Halsall's will directs his body to be buried in the parish church in the tomb made in the wall on the north side; £20 was to be distributed in alms on the day of the funeral; £98 3s. 4d. to his cousin John Halsall, son of James Halsall of Altcar, 'towards his exhibition at learning where my executors shall appoint': a brooch of gold with the picture of St. John Baptist thereupon to his nephew Henry Halsall; to Sir John Prescott, his 'servant and curate,' a whole year's wages; with other bequests. Any residue of his goods was to be given 'in such alms, deeds or works of mercy, and charity' as his executors might judge best. A codicil orders £4 13s. 4d. to be given for a chalice for the use of Halsall church, 40s. and 20s. towards the repairs of Melling and Maghull chapels. The inventory attached to the will shows a fair amount of plate, among it being the 'best standing cup,' called 'a neet,' garnished with silver and gilt, and valued at £5; Piccope, Wills (Chet. Soc.), ii, 35–9. 45 Paid first-fruits 6 Nov. 1563. Norris presented under the will of Sir Thomas Halsall. Cuthbert was ordained acolyte 17 April, 1557; see Lancs. and Ches. Records (Rec. Soc. Lancs. and Ches.), ii, 409; Ordin. Book (same soc.), 90. In 1572 Gilbert and Thomas Halsall, administrators and natural brothers of Cuthbert Halsall, late rector, sued Robert Amant of Downholland for £30; Pal. of Lanc. Plea R. 231, m. 12. 46 Paid first-fruits 10 May, 1571. 47 Paid first-fruits 20 Nov. 1594. 48 Institution not recorded; paid firstfruits on date given. He was also rector of Bury; q.v. 49 Institution Book; the Commonwealth incumbent is ignored. For the institutions and rectors see Trans. Hist. Soc. (New Ser.), xii, 241–52; Lancs. and Ches. Antiq. Notes; and Baines, Lancs. (ed. Croston), v, 272–5.

Dr. Matthew Smallwood, of the Cheshire family of that name, held Gawsworth in Cheshire and other benefices, and became prebendary of St. Paul's and dean of Lichfield. He is buried in the latter cathedral. Foster, Athenae Oxon. and references. 50 Nathaniel Brownell was an Oxford graduate; he is buried in Halsall church. He is described as 'an active and careful man; the restorer of both the church and the school.' He was returned as 'conformable' in 1689; Kenyon MSS. He had had a faculty for teaching boys in the school in 1680, so that he was probably curate for Dr. Smallwood. For further particulars, will, &c., see Ches. Sheaf (ser. 3), ii, 93, 98, 102; also W. J. Stavert, Study in Mediocrity. 51 The next rectors appear to have been of foreign birth. Albert le Blanc was made S.T.P. at Camb. in 1728, 'comitiis regiis'; and David Comarque was a graduate of the same university (B.A. 1720, M.A. 1726), being of Corpus Christi College; Graduati Cantabr. A Renald Comarque was made M.D. at the 'comitia regia' in 1728. 52 Dr. John Stanley was brother of Sir Edward Stanley, bart., who became eleventh earl of Derby in 1736; he had several benefices, and died as rector of Winwick in 1781. 53 Henry Mordaunt, son of Charles Mordaunt of Westminster, no doubt the patron, matriculated at Oxf. in 1750, aged eighteen, being of Christ Church (B.A. 1755). He was killed by falling from his horse. 54 Glover Moore was a local man, being son of Nicholas Moore of Barton. He matriculated at Oxf. (Brasenose Coll.) in 1756, when eighteen years of age, and graduated in 1760. He is called M.A. on his monument. 55 Thomas Blundell, son of Jonathan Blundell of Liverpool, was also of Brasenose Coll.; M.A. 1783; Foster, Alumni. 56 Richard Loxham was a Camb. man (Jesus Coll. B.A. 1783); he had previously been incumbent of St. John's Church, Liverpool. 57 Afterwards rector of Walton on the Hill. 58 A younger son of the patron. He was educated at Christ Church, Oxf.; M.A. 1860. In 1884 he was made canon of Liverpool, and in 1887 rural dean of Ormskirk and proctor in Convocation; also honorary chaplain to Queen Victoria 1892. He died 1 Nov. 1905. 59 Previously rector of Walton; q.v. 60 He was educated at Oxf.; M.A. 1520; B.Can. Law, 1532; Foster, Alumni Oxon.